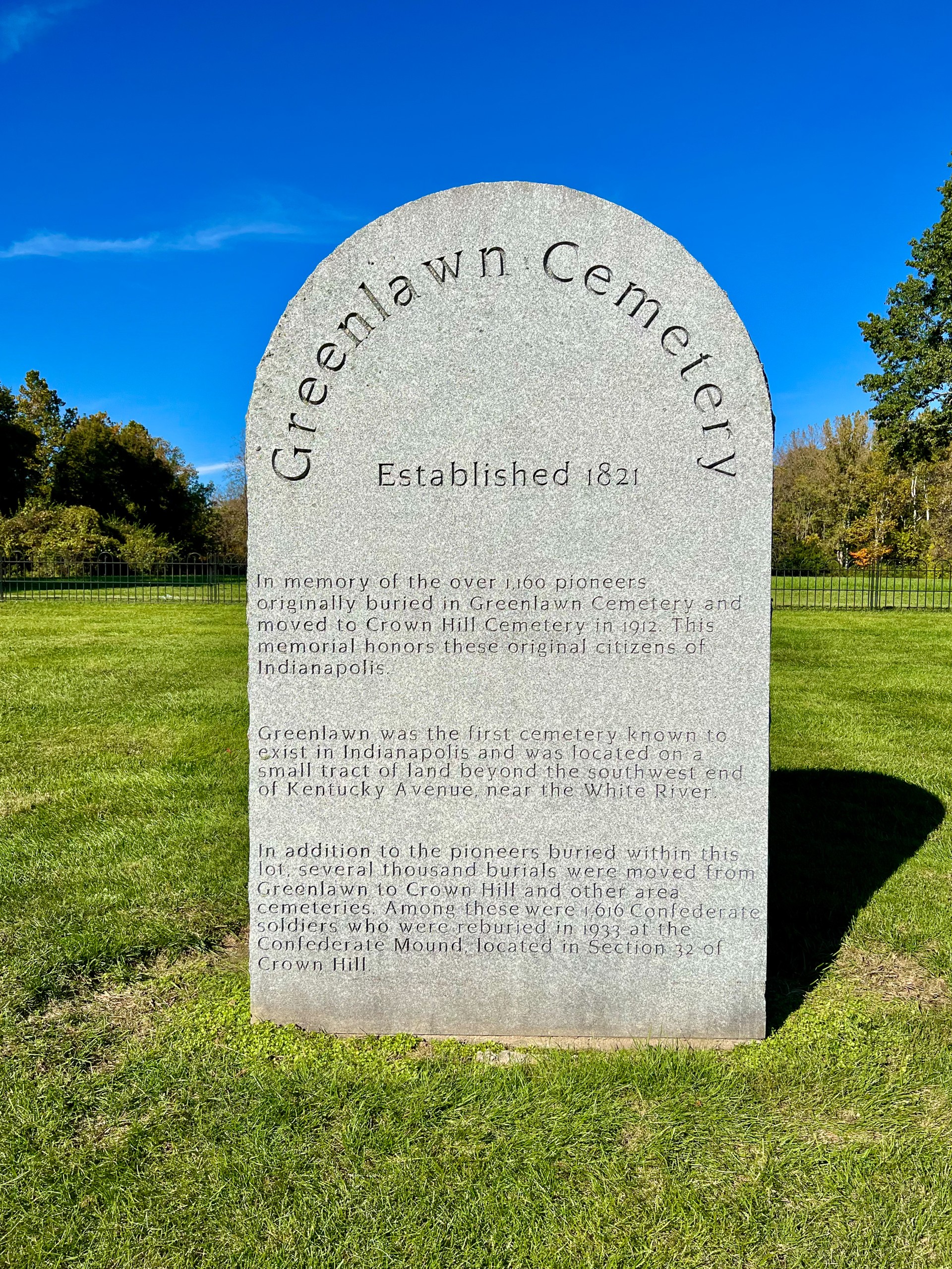

Greenlawn Cemetery

What cemetery is impacted?

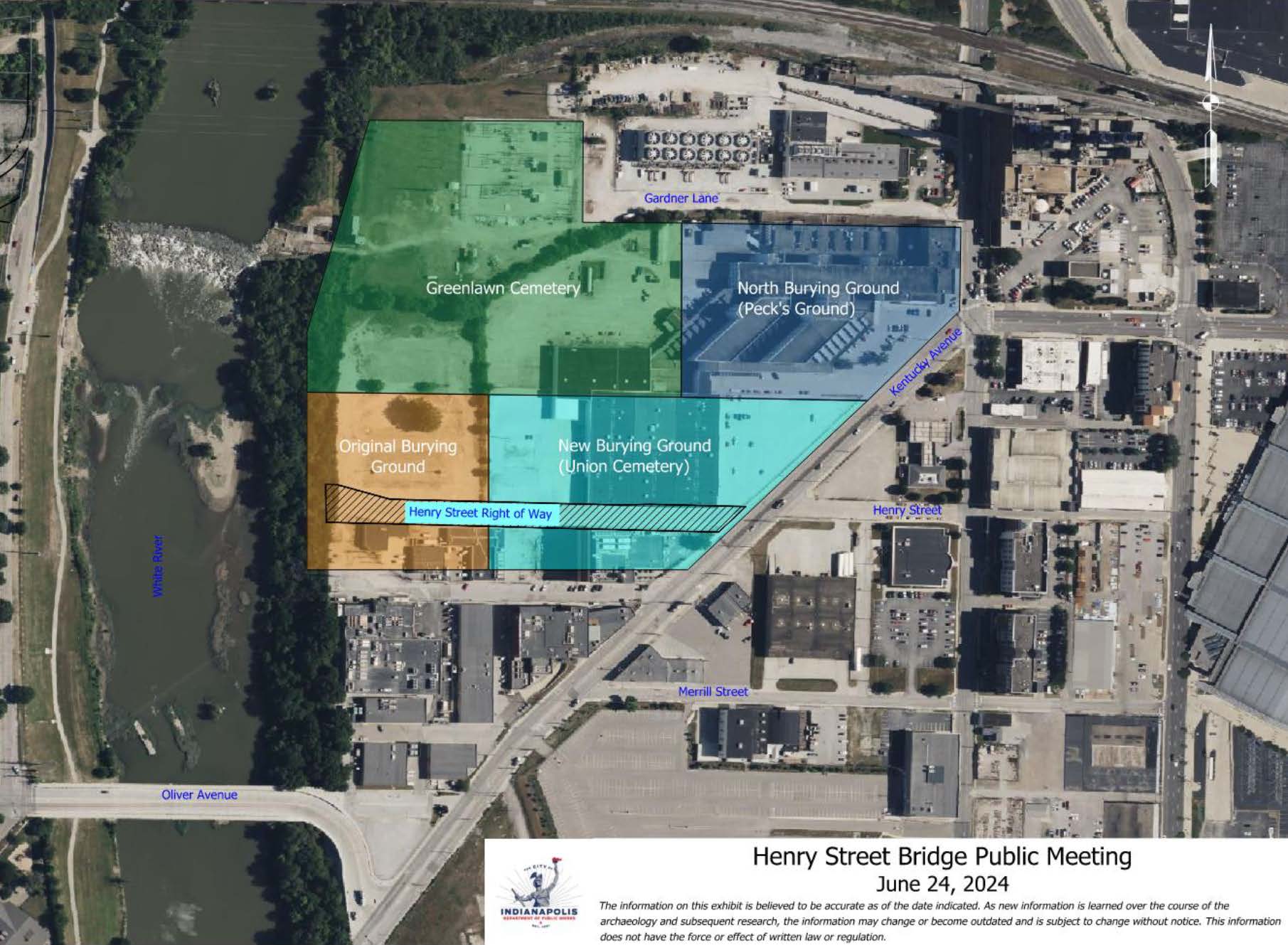

Portions of the burial ground called the “Burying Ground” (later called the “Old Burying Ground”) and the “Union Cemetery” (also called the “New Burying Ground”) are impacted.

Is Greenlawn one large cemetery or four smaller ones?

The name “Greenlawn” appears to have become associated with all four cemeteries around 1860. However, there were four separate areas. According to newspaper accounts, friends and families of the deceased could pick the location of the grave anywhere they pleased in the four acres of the old burying ground (Locomotive 1848). Private entities, however, owned the rest of the land within the burial ground and sold lots to citizens.

How much of the cemetery will be impacted by the project?

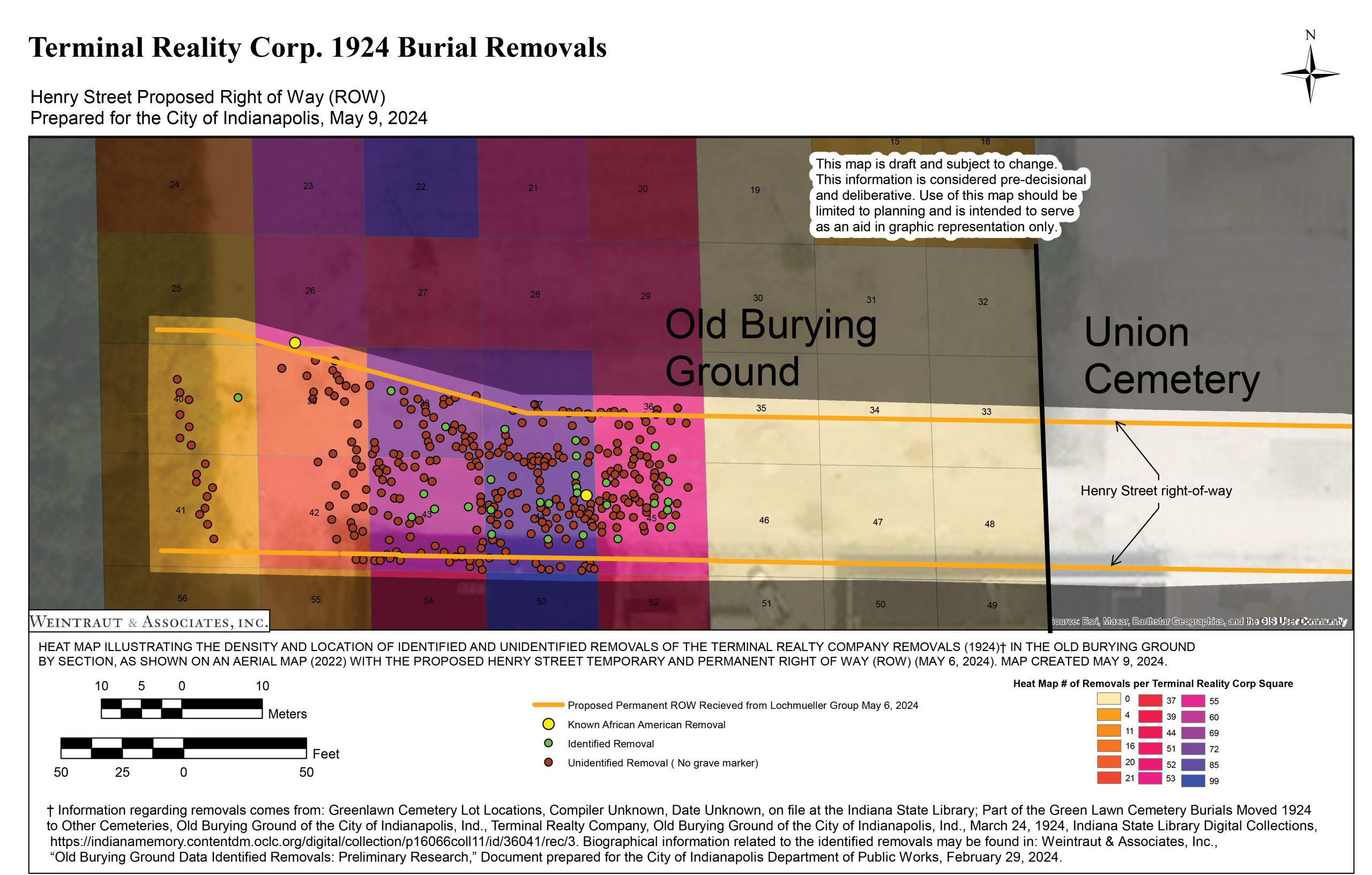

The Henry Street project impacts 1.359 acres of permanent right of way and 0.601 acres of temporary right of way. The map shows the location of the cemeteries* and Henry Street’s location within them.

Click here to download a copy.

Union Cemetery looking South to Henry Street, 1906 Bass Photo Collection, Indiana Historical Society

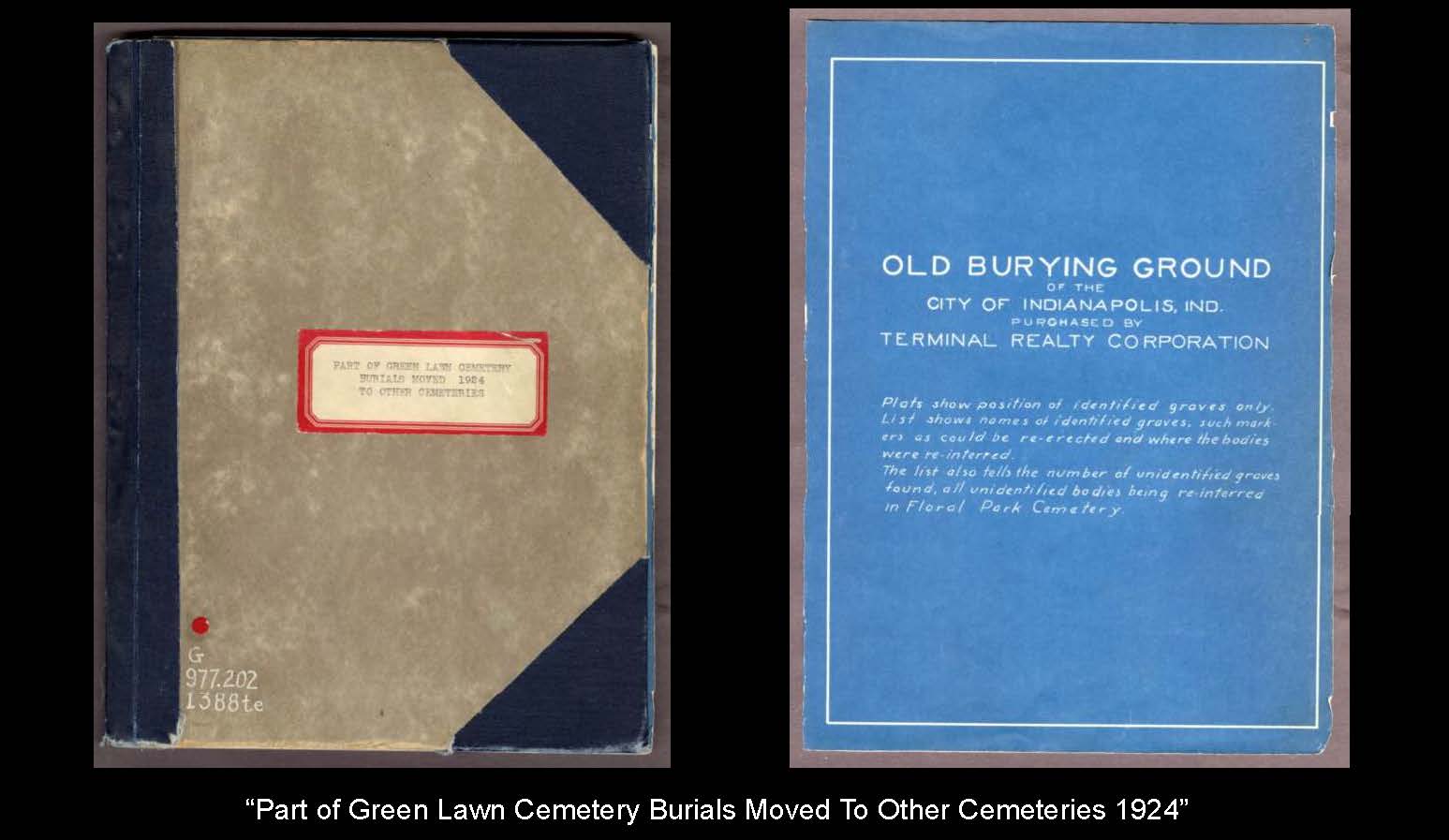

Part of Green Lawn Cemetery Burials Moved to Other Cemeteries – 1924

Terminal Realty Corp’s 1924 Burial Removals Map – 1924

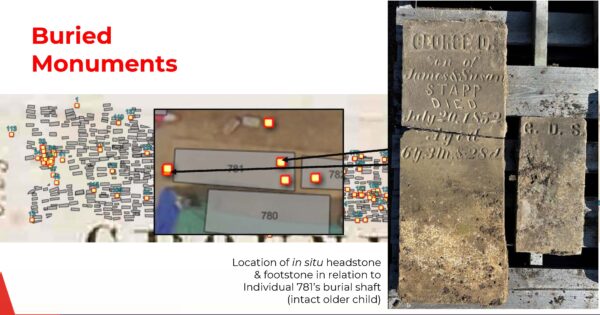

Many footstones and headstones were covered in place when the location of the former Greenlawn Cemetery was redeveloped

When was the burial ground appropriated?

In 1821, Daniel Shaffer, James Blake, and Mathias Nowland chose the site for a community burying ground (Nowland 1870: 35). In 1822, this choice was formalized when the General Assembly appropriated “as a public burying ground” on the four acres “known by the citizens of Indianapolis, by the name of the Grave Yard,” and directed the county surveyor to “survey, and lay off the same, wither in a square or in a parallelogram, as may best suit the situation of the ground” officially designating the area as the City Cemetery (Indiana Acts 1822-23 1823:28).

When did the earliest known burial occur?

According to research, Daniel Shaffer was the first person known to be interred in the burying ground in 1821 shortly after Shaffer, Blake, and Nowland chose the site (Nowland 1870: 35).

How large was the burial ground at its fullest extent?

At its fullest extent, the burial ground was larger than 25 acres.

An 1831 plat map (Indiana State Board of Accounts 1831: Index and page 31) shows the original “Grave Yard” location. The Grave Yard has been known by various names over time, but its four-acre square on 19th-century maps has generally remained constant.

Later additions to the cemetery included Union Cemetery’s five-acre plot in 1834; Siter Price & Co.’s 8.5-acre addition in 1838 (called Green Lawn Cemetery on plats prepared in 1860); and E.J. Peck’s 7.5 acres in 1852 (Holloway 1870:261). By 1852, the area known as “City Cemetery” contained more than 25 acres, encompassing the original four-acre “Old Burying Ground” (adjacent to the White River) and three additions.

According to Sulgrove’s History of Indianapolis, the area known as the “Old Burying Ground” (about four acres) became the burial location for poor Euro-Americans and for African Americans once the Union Cemetery was laid out into regular plots (Sulgrove 1884:385; Holloway 1870:79).

Why was Greenlawn Cemetery abandoned?

Crown Hill Cemetery was established in 1863 and began accepting burials. Around that same time, the old burying ground was becoming increasingly crowded and also faced maintenance issues. Subsequent years saw a failure of the cemetery’s private owners to maintain the graveyard (Indianapolis News 1874).

In 1890, however, the Indianapolis News reported there were still unauthorized burials occurring there (Indianapolis News 1890), and that same year, the City of Indianapolis made it unlawful to bury or inter dead bodies there. Despite that ordinance, families persisted in burying their dead within the cemetery (Brown and Thornton 1904:938-948).

In 1894, the City passed another ordinance declaring the Greenlawn Cemetery and tracts adjacent to it a public nuisance. In the ordinance, the City described the cemetery’s state of “decay and neglect,” declaring that it has become the “resort of evil persons, who thereby escape police surveillance and arrest, and also there indulge in lewd, vicious and immoral conduct….” (Brown and Thornton 1904:938-948). The ordinance required the removal of fencing and the cutting and trimming of enough vegetation to return the cemetery to good order. Additionally, it required the removal of all corpses and other contents from vaults, followed by the removal or destruction of vaults. If the owners did not comply with the removal order, the City of Indianapolis authorized the Department of Public Works to remove and destroy vaults at the expense of owners. Additionally, if no owners were located, it authorized the Department of Public Works to proceed as if the owners had been found and failed to comply (Brown and Thornton 1904:938-948).

Has this burial ground been impacted before?

The area of the Henry Street project has undergone much disturbance over the past 125 years.

Are there records of known large-scale burial removals within the Henry Street right of way (impacting the Old Burying Ground and Union Cemetery)?

Yes, while research is ongoing into additional relocations, DPW has obtained Terminal Realty Corp.’s 1924 Burial Removals map (see image) for grave relocations within the Old Burying Ground. Terminal Reality Corp undertook the relocations with the objective to reuse the ground. The map only represents relocations in the Old Burying Ground; no similar information has been found for the Union Cemetery.

The colors of each grid represent the number of known removals within in each grid. Each individual removal is further represented by a dot. Some grids have no documented removals as shown with the pale yellow grid color (on the east side of the Old Burying Ground). For the Union Cemetery further to the east, no documentation of large-scale burial removal has been found.

Were human remains encountered prior to Stantec’s archaeological investigation? How were they handled?

During subsurface utility excavation on July 18, 2023, an isolated human skeletal element was found by archaeologists inspecting soil in the vacuum truck holding tank. Learn more about that discovery.

There have been accidental discoveries of human remains within the boundary of the larger burial ground since the 1930s. It is presumed that those accidental discoveries were handled in accordance with laws in effect at that time.

Was anyone famous or historically significant buried there?

Early settlers, prominent local citizens, and public figures were said to have been buried in the cemetery. During the Civil War, around 1,600 Confederate soldiers who had been prisoners of war from Camp Morton, as well as approximately 1,300 Union soldiers, were reportedly interred there. The exact location of Civil War soldier burials is unknown.

One of the more well-known figures is Alexander Ralston, who laid out the plat for Indianapolis, and was said to have been buried in the cemetery. In 1891, The Indianapolis News reported that there were different accounts of what happened to Ralston’s remains. It had been reported that Ralston was removed and reburied at Crown Hill, while someone else claimed that those were not Ralston’s remains at all. The newspaper also noted that if Ralston’s remains were still in the cemetery, they were probably in the “portion eaten away by the river” (The Indianapolis News, “Where is Ralston’s Body!” 1891).

Presently, the Community Advisory Group is conducting research into Black burials within the cemetery. This research will be made public.

What happened to the graves of the Civil War soldiers?

The graves of Union soldiers began to be moved to Crown Hill Cemetery shortly after the end of the war, but it would not be until 1931 that the Confederate soldiers were moved to a mass grave at Crown Hill (DeMore 1977:12-14).

Click here to see references and additional FAQs about the project.

*The information on this website is only intended to be general summary information to inform the public of the status of the archaeology at the relevant site. The information on this site should not be used for any purpose beyond general, informational purposes. The information on this site is believed to be accurate as of the date it was added to the website. As new information is learned over the course of the archaeology and subsequent research, the information on this site may change or become outdated and is subject to change without notice. This information does not have the force or effect of written law or regulation.